Reflections on Teaching Flipped Calculus

This past semester (Fall 2019), I taught “flipped calculus” for the first time at UVA. It was a whirlwind experience with many challenging but also rewarding aspects. As one professor told me “I do not want to hear your abstract teaching philosophy” and so I wish to clarify that this write-up is merely a reflection on my experiences and lessons learned while teaching this new classroom model; it is not meant to be didactic.

How class worked

The key idea behind “flipped calculus” is that students do their initial learning of concepts outside of class so that class time can be used to build on that prior learning by tackling more advanced concepts, working on problem solving, and practicing communication skills. To students and teachers of the humanities, this sounds like nothing novel; many humanities classes I took as an undergrad required reading outside of class that involved encountering new concepts for the first time and subsequently discussing and expanding on the new material in class. In contrast, math and science classes have traditionally been taught in lectures that introduce new concepts in class and then require students to do the more in-depth learning outside of class. Thus, flipped classrooms attempt to reverse—or flip—the traditional teaching model for math in ways that are not dissimilar to how many humanities classes are taught. However, this is not merely conceptual: there is a decent amount of research on teaching calculus in a flipped classroom, such as “The Calculus Concept Inventory—Measurement of the Effect of Teaching Methodology in Mathematics” by Jerome Epstein, that argues students learn better in flipped classrooms.

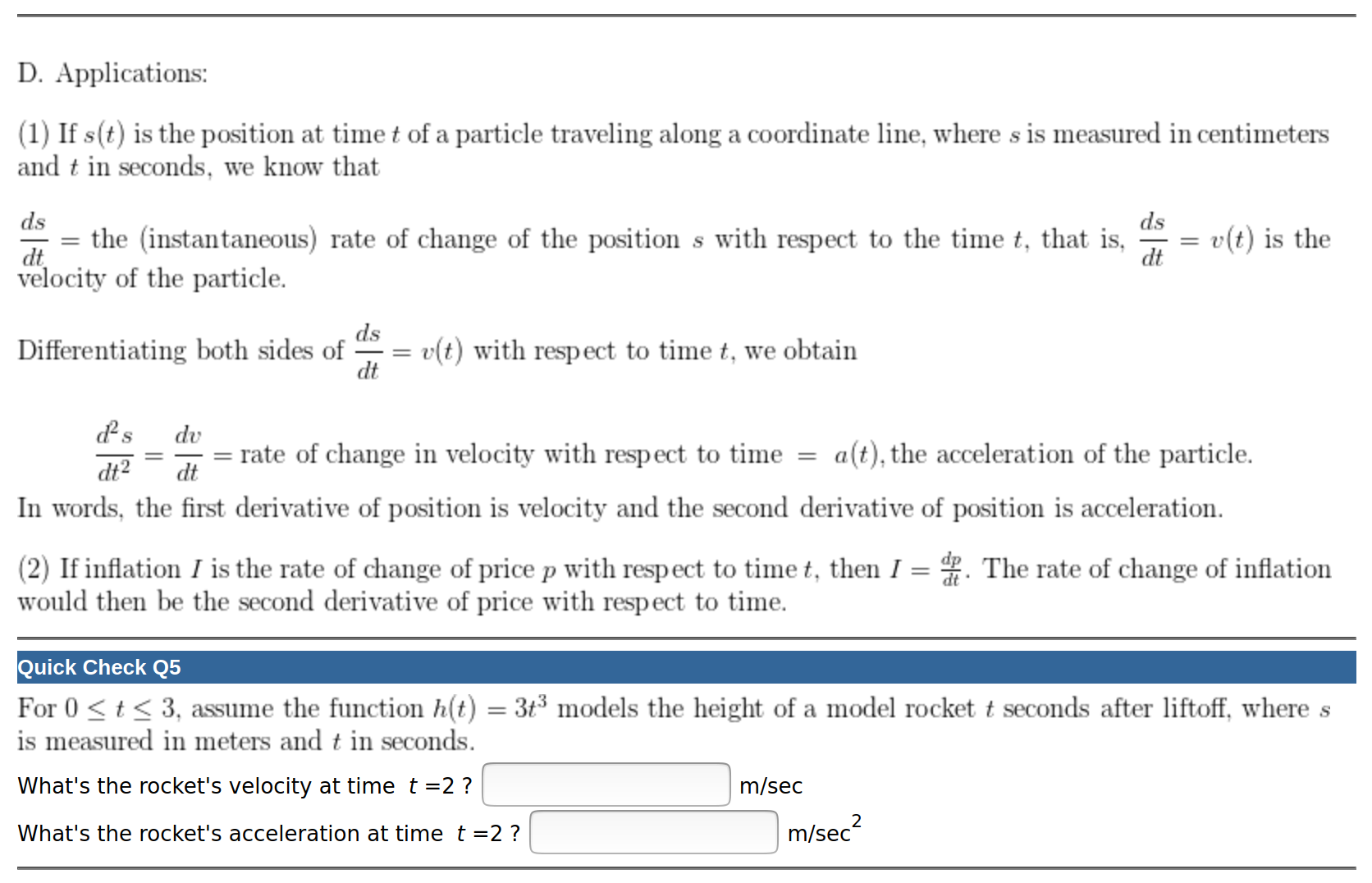

To facilitate this flipped model in my class, students were given “class prep” assignments via an online homework system called WebAssign that contained readings, explanatory videos, and “quick check problems” students could use to instantly check their understanding. Then, class would start with about a 5 minute recap in which I would ask students to volunteer information which they learned and I would summarize or add to what they voiced, often trying to provide a picture of the situation or a specific example. After this quick recap, students would be given worksheets which they were to complete in pre-assigned groups for the majority of the class period. During this time, I would walk around the classroom, listening to the group conversations and answering questions if groups got stuck. I would also solicit student presentations of problems I felt particularly difficult or illuminating and prompt the class to ask questions both about the mathematics and how the student communicated their solution in writing.

I think one cannot understate the importance of these presentations, despite the fact that students were, at best, luke-warm to the possibility of presenting in front of the class. The idea behind the presentations is that they give students a chance to see complete and well-structured solutions to the problems they are working on, as well as giving students affirmation that their answers were indeed correct. It also opened up the floor to discuss expectations for what work should be shown on an exam. However, such discussions did not happen naturally. I quickly learned that asking “any questions?” was a certain way to make sure no questions were asked. Instead, I asked students to share any of the following:

- Did anyone solve or approach the problem in a different way?

- Did anyone run into any pitfalls while solving this problem?

- Does anyone see anything someone could forget to do on an exam?

I would try to be flexible with how I let students present, often letting students present in pairs or as an entire group, as well as providing affirmation that their solution was reasonable or correct if they asked for it. However, I was firm that presentations had to happen and I had students present in almost every class where I gave a worksheet. Finally, at the end of every class, electronic copies of the worksheet and its answer key would be posted online for students to study on their own any of the problems that were not presented in class.

An excerpt from a class-prep assignment.

Reflections and Discussion Section

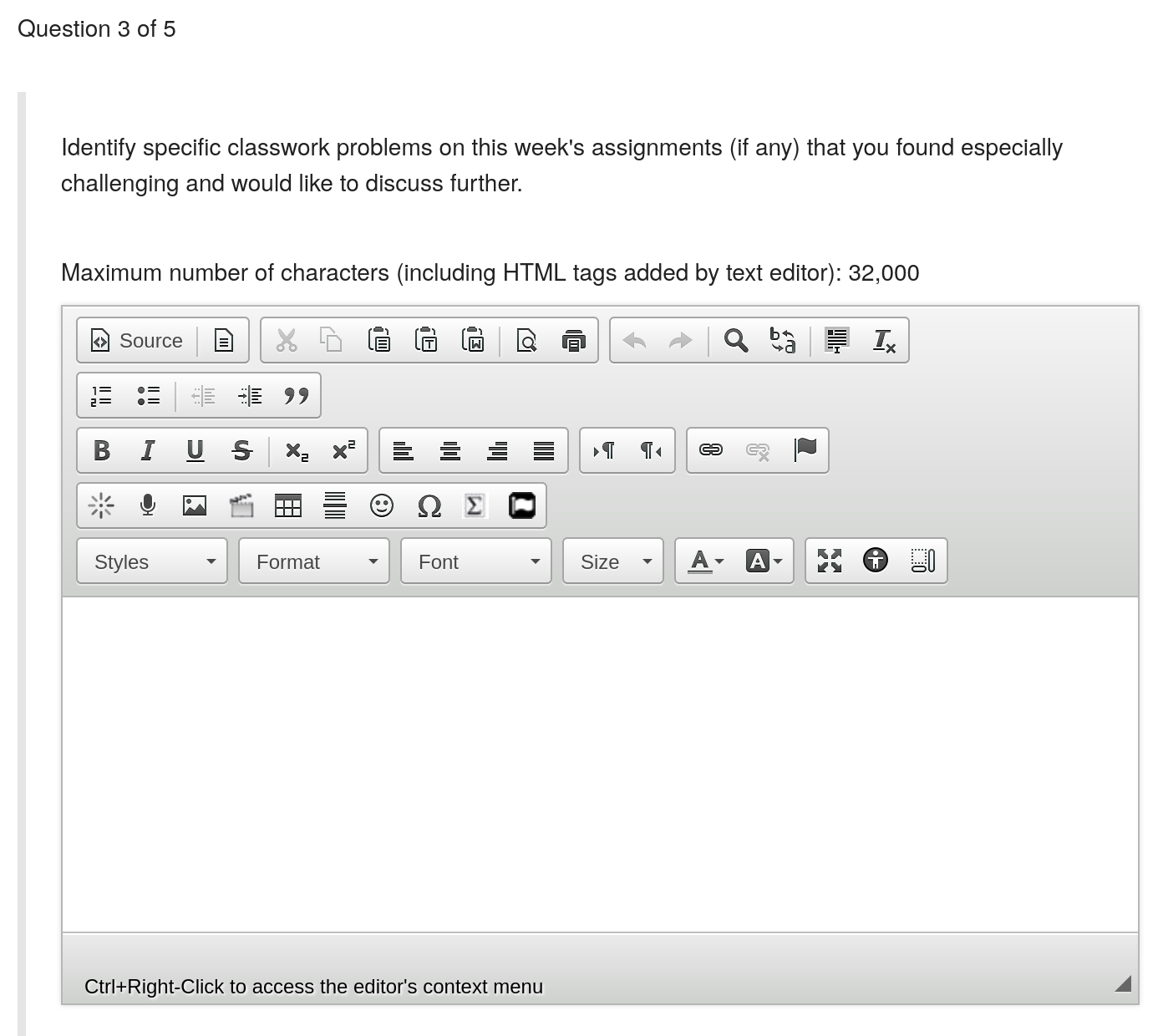

At the end of every week, students would be asked to complete online reflections in which they reflected on what they had learned, what they were still confused about, and how their groupwork was going. I would read students responses and found them helpful for gauging how students were learning material and feeling about the course. There would then be a “fourth hour” discussion section that operated more traditionally. During this time, I would try to recap material learned during the week that students had asked questions about in their reflections, as well as answer any questions raised in the classroom. This was also the time period when I would give a quiz. Many students expressed to me (via the reflections) that they found this meeting essential to their learning since it gave them an additional opportunity to reinforce that week’s material. One challenging aspect of the course for the students is that the quiz would be on topics covered that week, although the quizzes accounted for a small part of their overall grade and students were offered an optional take-home quiz they could complete over the weekend to bolster their in-class quiz scores.

An example reflection prompt.

The Importance of Groupwork and Changing Groups Frequently

The groupwork proved to be critically important in the course. I felt that groups provided a sense of camaraderie among the students, but crucially also enhanced their learning. Often students would remind each other of concepts or techniques (e.g. a function with a positive derivative is increasing) and engage in important discussions, such as when they could use particular theorems (e.g. since this question is only asking if a value exists, we can use the intermediate value theorem). The prevailing wisdom is that such discussions reinforce these concepts better than if students are only hearing the concepts from their instructor (see, for instance, “Combining Peer Discussion with Instructor Explanation Increases Student Learning from In-Class Concept Questions” by Smith et al.).

I also found it important to change groups frequently, especially early on. The idea behind group switching was that students could become more comfortable working with and presenting to many of their classmates. It also attempts to disrupt students falling into grooves such as having one student carry the other group members. Based on the worthwhile mathematical conversations I would frequently overhear in class, I also believed students could learn a lot from each other, so it was good to expose each student to many of their other peers. Finally, it was a joy to watch students develop genuine friendships in class.

Student Buy-in

At first, many students expressed a lot of resistance and displeasure towards the flipped model. Instructors and researchers almost unanimously notice this resistance and have tried to measure and understand it, such as in the study “Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom” by Deslauriers et al. where researchers observed that, even as students learned more, they felt like they were learning less. I saw this article early on during my semester and tried to continually implement its recommendation that instructors should “intervene early on by explicitly presenting the value of increased cognitive efforts associated with active learning.” Our course coordinator was also aware of such issues and encouraged us to explain the mechanics of the course and remind students throughout the semester why we implemented these mechanics. The article suggests that instructors “give an examination as early as possible” so students can see they are actually learning. My experience was that students indeed felt more comfortable with the course structure after their first midterm. Afterwards, students seemed to outwardly become more accepting of the flipped model, if not enthusiastic. Unfortunately, upon reading my course evaluations, it seems that many students still felt that they may have been more satisfied with a lecture, although a few expressed satisfaction, too. Finally, students rated their course satisfaction above the UVA Math Department average on likert questions.

Coordination

At UVA, all sections of flipped calculus are coordinated to have the same in-class worksheets, homework assignments, and exams, as well as the same opportunities for extra credit. Instructors only have control of about 10% of the students’ course grades in the form of approximately 10 weekly quizzes. On the one hand, it is quite helpful to already have so many well-tested and high quality class materials ready to go, but it also presents a unique set of challenges when the materials emphasized or de-emphasized different concepts and skills than I would have. This also created quite a bit of administrative overhead. It took the syllabus template 6 single-spaced pages to describe everything to the students. So, to keep my class running well, I would send my class at least one email with reminders about every other week and I would take class time to remind students of everything they needed to keep in mind. I found that my general guiding principle for these administrative issues was that redundancy is key. Reminding my students of their responsibilities frequently meant that students got everything done on time and I hope without feeling too overwhelmed.

Syllabus

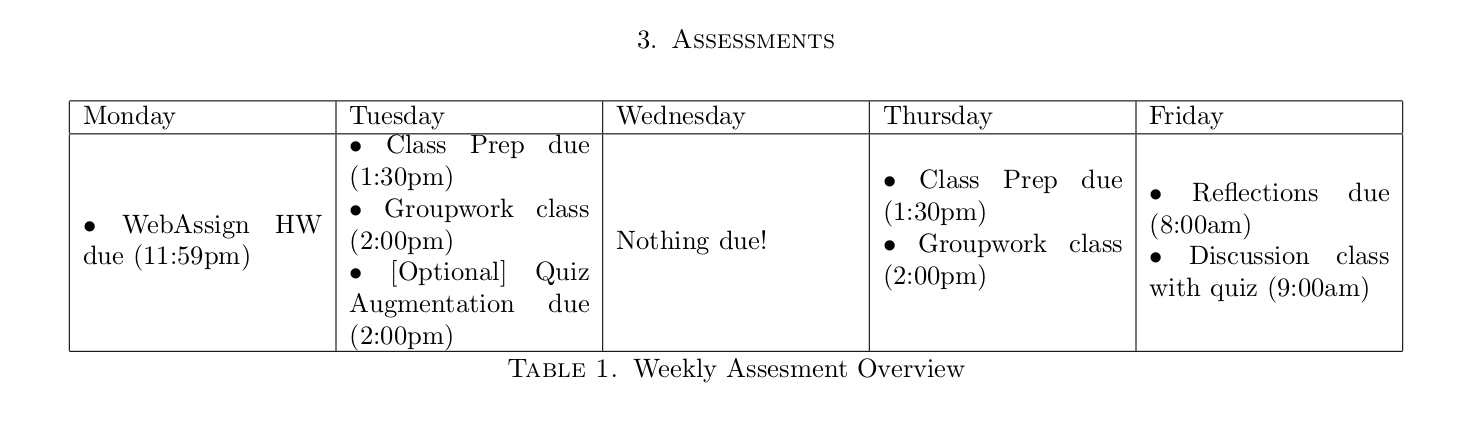

Because there were so many course components, I found it important to have a well-explained syllabus. As mentioned above, the material we were required to put on our syllabus took up 6 single spaced pages. However, after reading a blog post on the AMS PhD + Epsilon on Creating a Motivational (Math) Syllabus by Alexander Diaz-Lopez, I decided to not be afraid of long syllabi. Instead, I decided to expand the syllabus by adding section/subsection headers and a table of contents, along with adding some tables and graphics where I thought they might be helpful. (Link to my syllabus). Of course, I have no empirical way of knowing if this really helped my students or not, but it made it easier for me to refer to my own syllabus and to help answer common student questions. Finally, since I knew the course components were difficult to keep track of, I was always happy to revisit and reanswer student questions about course logistics.

A table added to my syllabus to summarize weekly tasks

Flipped versus Lecture

Of course, the big question is whether or not the flipped model leads to better learning outcomes than lecture courses or not. However, since this is not meant to be an abstract teaching philosophy, I will leave that question to math education researchers. Instead, I will point out the differences in my experience as an instructor.

- I found teaching flipped calculus incredibly enjoyable in the classroom. I felt I was better able to connect with students and continuously gauge their strengths and weaknesses.

- Teaching flipped calculus in a coordinated setting definitely required less preparation work for class because the worksheets and answer keys were already constructed to match the pre-selected WebAssign class preparation homework assignments.

- However, the class required much more administrative work on my part outside of the classroom. I tried to automate as much of the work possible, but I had to make sure to post materials and their answer keys online after each of the three meetings every week.

- Furthermore, my idle thoughts often drifted towards making sure I emphasized or explained ideas correctly to my class. When teaching a lecture, I could spend time before class to make sure the explanations were tight and agreed with expectations for the exams. However, in a flipped classroom, I spent more time answering questions than teaching prepared materials, which meant my explanations were more off-the-cuff.

- I found the flipped timeline difficult to keep up with at times. In particular, my students filled out their reflections between 3:15pm on Thursday and 8:00am on Friday. Then, I would read the reflections and build our 9:00am Friday meeting around these reflections. The tough part was that I only had one hour to absorb and build upon these reflections.

- I felt I was able to connect with my students more personally in the flipped classroom. Also, a much larger proportion of my students attended my office hours when teaching flipped calculus. However, it is unclear how much of this is due to the flipped model and how much is due to smaller class size.

These are just some of my observations after teaching one semester of flipped calculus; there are many more well-thought out accounts and empirically driven studies out there, such as the materials I referenced. In conclusion, I would certainly be happy to teach a flipped classroom again, although I believe it would be more difficult without broad institutional support.

References

- Braun, Benjamin, et al. “What does active learning mean for mathematicians.” Notices of the American Mathematical Society 64.2 (2017): 124–129.

- Deslauriers, Louis, et al. “Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116.39 (2019): 19251-19257.

- Diaz-Lopez, Alexander. “Create a Motivational (Math) Syllabus.” AMS Blogs: PhD + Epsilon (2019). https://blogs.ams.org/phdplus/2019/07/08/create-a-motivational-math-syllabus/

- Epstein, Jerome. “The calculus concept inventory-measurement of the effect of teaching methodology in mathematics.” Notices of the American Mathematical Society 60.8 (2013): 1018–1027.

- Smith, Michelle K., et al. “Combining peer discussion with instructor explanation increases student learning from in-class concept questions.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 10.1 (2011): 55–63.

Date published: Sunday, February 2, 2020